A version of this tribute was first published at ReligionUnplugged.com

The world has lost a witness to the counter-narrative of love and service that is possible between people of different races with the death of my friend David Jowitt.

I knew David for more than twenty years and was always fascinated by his ability to live an entirely Nigerian life. Professor of English at the University of Jos in Plateau State in Nigeria, he was the last British person in the university system there. The university closed in mourning on news of his death, which took place during his annual trip to London.

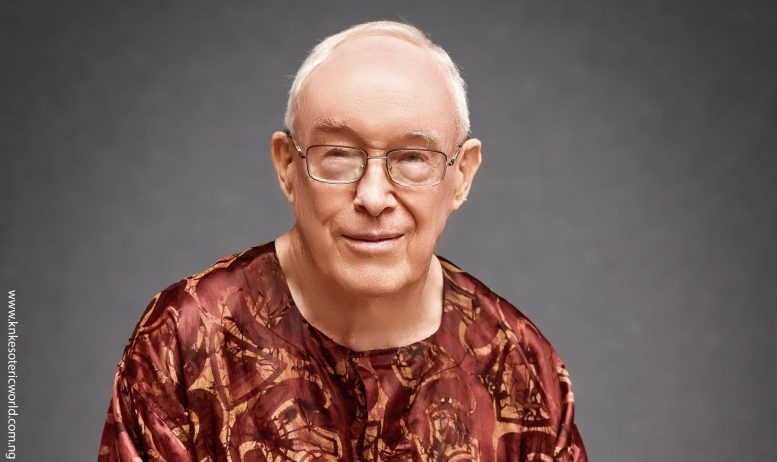

Professor David Roger Jowitt

He wrote the definitive Longman textbook “Nigerian English Usage” — but his greatest ambition was to become a citizen of Nigeria, a wish that was realized at a ceremony in Jos on June 12 at the age 82, just two months before his death.

David’s ashes, at his own request, are buried in Jos at the Augustinian seminary.

READ: Britain’s Faith Museum And 6,000 Years Of History

The significance of this was noted by eminent writer Abubakar Adam Ibrahim in a recent article for the Nigerian newspaper Daily Trust: “His story is a remarkable counter-narrative to the Nigerian exodus story. When many Nigerians are giving up on the country, here is an 80-year-old man who is not.”

David, who was born during a German air raid, was a volunteer relief worker and witnessed the Nigerian civil war in Biafra.

Thanks to a contact with then-Anglican Archbishop of West Africa, the Revd C.J. Patterson, he was taken on as a teacher with the Church Missionary Society in newly independent Nigeria.

He served there for two years at the Anglican Grammar School in Ubulu-Uku, Delta State, from 1963 before being forced home by the war.

David’s gift for “going the other way” was demonstrated, however, when in 1969 he volunteered to go back to Biafra as a relief worker with the World Council of Churches. He helped organize the evacuation of aid workers under shell fire from Owerri, managing to get the last plane out of Uli on Jan. 10, 1970, before the airport was bombed.

The son of a delivery driver, David epitomized the reality of British social mobility. He grew up, along with his two sisters, in a rented ground floor apartment on a deprived estate in Wood Green, north London. His father worked as a driver for 45 years for what became the Eastern Electricity Board; his mother had been a seamstress before their marriage. He described his upbringing later as “limited” but loving.

His father, he wrote in his memoir, did not know what a university was. But David was gifted with a good memory and a passion for the dates of kings and queens of England. A discerning teacher at Stationers’ Grammar School, since demolished, steered him towards the Oxbridge entrance exams. He won an exhibition to Magdalene College, Cambridge, to study history. It catapulted the “impressionable” David into a new social echelon — and he maintained friendships with the British journalist Benedict Nightingale, the Catholic philosopher John Rist and his first Nigerian contact, the Rev. John Ohen, for the rest of his life.

He had always regretted that he only achieved a second-class degree. Characteristically it served to make him more determined, and he studied and found a love for esoteric linguistics in which he gained an master’s degree from Essex University, though never a doctorate.

He returned to Nigeria for a third time in 1974 and discovered his life’s calling — a passion for lecturing to young adults. He was appointed professor at Bayero University, Kano, in the north of the country in 1987. By 2003, he was the last British person working in the Nigerian University system.

David was in Nigeria longer than most Nigerians, where a majority of the population is under 30. In the course of 60 years, he travelled and lived all over the country — places like Onitsha, Ibadan, Zaria and Kano — where the heat eventually drove him south again to the cooler plateau town of Jos. He also had spells working in Libya and even had a short stint running the Africa Centre in London.

David had a gift for friendship and was beloved by his students, many of whom he helped from his own pocket. Several friends — including the vice chancellor of Jos University — flew to London for his funeral. He was hurt more by white racism than black because he believed it “mixed ignorance with contempt.”

He was always gently amused by the attitudes and English of his adoptive country. It prompted first a book, “Mistakes in English,” then — when he came to see and respect the fact that Nigerians had not only adopted the English language but made it their own — he produced the book “Nigerian English.”

Three years ago, he was elected a fellow of the Nigerian Academy of Letters in recognition of his contribution in the development of education as a whole in Nigeria. David, who was never married, but longed to be, dedicated his memoir to Nigeria. He described the country as his “mistress” and his “great love.”

An Anglican, David became a Catholic in February 1992. He remarked that “my colleagues in the Department were nearly all Muslims. … They knew that I was a Christian, however, and it touched me that, more than once when a departmental meeting took place and an opening prayer was needed the Head of Department asked me to say one.”