THE spectacular six-hour “outage” of Facebook’s multiple platforms on Monday evening [4 October) threw much of the world into a flap.

More than a third of the planet – 2.8 billion people – log on to Facebook, WhatsApp or Instagram each day. From MPs wanting to respond to Brexit minister Lord Frost’s speech at the UK Conservative Party Conference, to the woman selling children’s clothes on Facebook in Nairobi cited by The Telegraph, to me in my bedroom puzzled by an unfamiliar “no send” icon on WhatsApp messages to family about my father’s interment next week, we were all united in this curious communications failure. It was a minor bereavement that we shared with people across the globe.

Writing in the context of public theology, one has to ask, is that a good or a bad thing: not the outage per se, but the simultaneous universal experience of a technological moment in time? It is certainly a phenomenon that should be questioned.

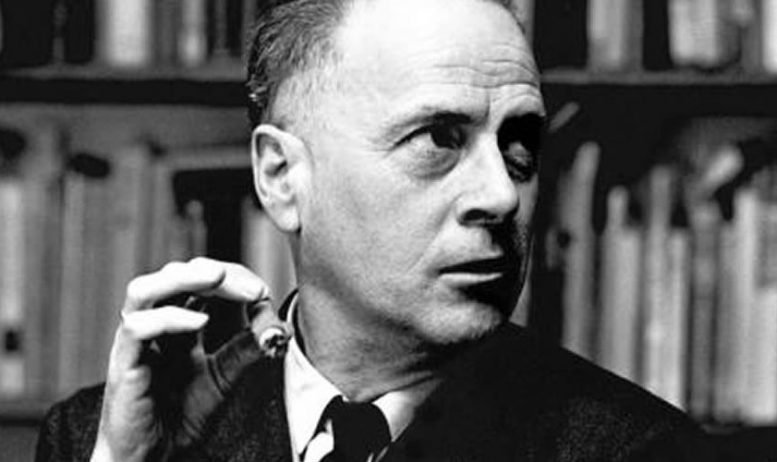

Not a good one, Marshall McLuhan would probably say. “The medium is the message”, said the late author Understanding Media, who was very exercised by radical communications change.[1] He believed we have as Christians very little sense of – and a curious lack of interest in – what novelty in communications experience on a vast scale does to us; but doing something it definitely is.

The ancients attributed godlike status to all inventors since they alter human perception and self-awareness. The same principle of complementarity and metamorphosis of our identity image in relation to technologies is neatly summed up by German physicist Heinrich Hertz in the following epithet: “the consequences of the images will be the image of the consequences.”[2]

And just what is that image? For McLuhan, an American teenage convert to Catholicism, and Cambridge-educated prophet-celebrity-scholar who died in 1980 before social media had dawned,[3] it would be decidedly diabolic.

He called the electronic media environment “Luciferan” – as in mimicking light and goodness, and that was before Facebook and Twitter. In a letter to a priest friend, he wrote: “… it is ethereal and a highly plausible mock-up of the mystical body”. It looked like light, but was anything but, he felt. That was in 1969.

He dubbed electric technology “the environmental extension of our own nervous system”. And wasn’t that precisely how it was on Monday, when nearly half the world twitched nervously at the same moment? And Facebook’s share value reflected it by falling by £37billion.

So the medium really is the message: and the message for McLuhan is blasphemy. The electric information environment’s being utterly ethereal “fosters the illusion of the world as a spiritual substance” says McLuhan. It is now “a reasonable facsimile of the mystical body, a blatant manifestation of the Anti-Christ.”

By that I take him to mean a fake communion. Only the real thing is life-giving; the rest is subtly destructive.

And even if that goes too far – and many have recently been pointing out the benefits for the non-Western world of being able to market, to trade and to opinionate free [somewhat] of totalitarian controls – you must wonder what is happening to our psychokinetic and spiritual “at-oneness”.

Do we lose our sensitivity to the microscopic vibrations of the soul attuned to God’s own messengers, the angels, and their inexplicable nudges to pray in someone’s hour of need? Are our very souls not arrested by a money-driven advertising medium that lies when it purports to do us good? Do the “relationships” fostered merely feed the beast i.e. fail truly to nourish, but just create more hunger?

For McLuhan such questions are not asked anything like enough, and rarely have been in history. But they should be, for there is a down-side to every innovation: we lose as we gain.

With the car for instance, “greatly increased mobility simply erases many forms of community as we have known them,” he says. With the Gutenberg revolution, for another instance, print fragmented our ability to hear (as opposed to merely listen to) the Church, and ended up dividing us into myriad fissive protesting sects.

McLuhan does not condemn these developments, or at least he sometimes appears to condemn them out of hand, but years later baffles us with nuance that can give the impression of voltes faces; then he says he really just wanted us to sit up and notice the effects.

He has a point. For as historian Elizabeth Eisenstein pointed out in 1979, it took more than five hundred years for the broad impacts of the print revolution to be studied.[4]

“What were some of the most important consequences of the shift from script to print?” – asks Eisenstein. She goes on: “Anticipating a strenuous effort to master a large literature, I began to investigate what had been written on this obviously important subject. To my surprise, I did not find even a small literature available for consultation. No one had yet attempted to survey the consequences of the fifteenth-century communications shift.”

Astonishing but true, not least because so much of our world including such seismic changes as the very idea of nationhood for one, would not have been possible without print.

How much more crucial then for Christians to understand better the deep structural, psychological and spiritual changes wrought by the phenomenon that has just shaken the whole world at once – Facebook?

[1] Understanding Media: the Extensions of Man (London: Sphere Books, 1967 et al).

[2] From the Introduction (p. 2) to The Principles of Mechanics (1956), translated by D E Jones and J T Walley, cited in E. McLuhan and J Szklarek, The Medium and the Light: Reflections on Religion (Toronto & New York: Stoddart, 1999), 71.

[3] Facebook was launched in 2004.

[4] There was no discipline of “print studies” until Eisenstein’s heroically pioneering The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979).